On the history of black bodies in anatomical imagery, and The Good Point Project

Research on the history of anatomical imagery of acupuncture is scarce. There are some references, but very little work has explored the representation of non-white bodies in acupuncture. However, as all histories of medicine are interconnected, and with the intention to present a design intervention that is US-based (The Good Point Project), we could argue that the omission of women of color from acupuncture diagrams can be understood within a longer history of race and gender in anatomical and medical representation across cultures and differences.

The representation of Black women's bodies in medical and anatomical illustrations has long been entangled with histories of colonialism, exploitation, and systemic racism. Medical science, particularly during the 18th and 19th centuries, often used the bodies of enslaved and poor Black women for experimentation and education without consent. For instance, the work of Dr. J. Marion Sims, often celebrated as the “father of modern gynecology,” involved non-consensual surgeries on enslaved Black women without anesthesia. Moreover, anatomical atlases, medical illustrations, and educational diagrams often depicted Black women in distorted or exaggerated ways, reinforcing pseudoscientific ideas about racial difference. These representations were typically created by white male artists and physicians for white male audiences, further entrenching the racial and gender hierarchies of knowledge production.

Recent scholarship in medical humanities has highlighted how these visual traditions persist, even in contemporary health education. The invisibility of marginalized bodies in anatomical design today is thus part of a broader legacy of epistemic and material injustice.

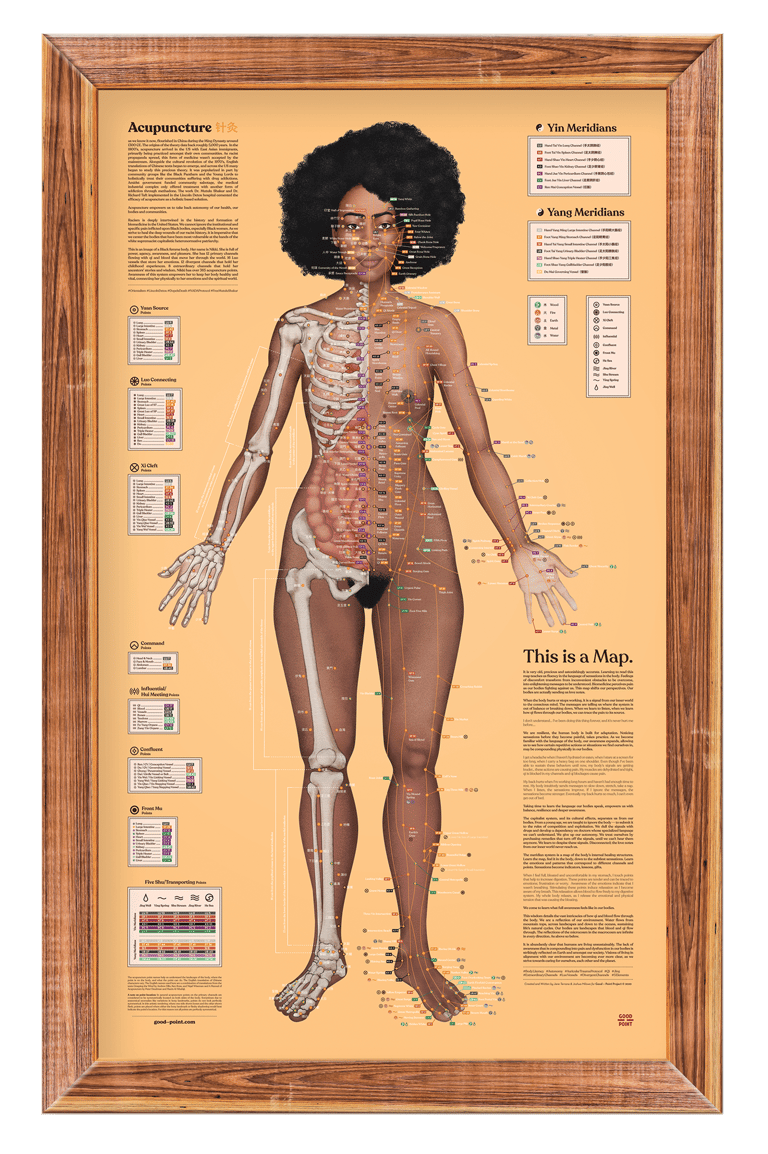

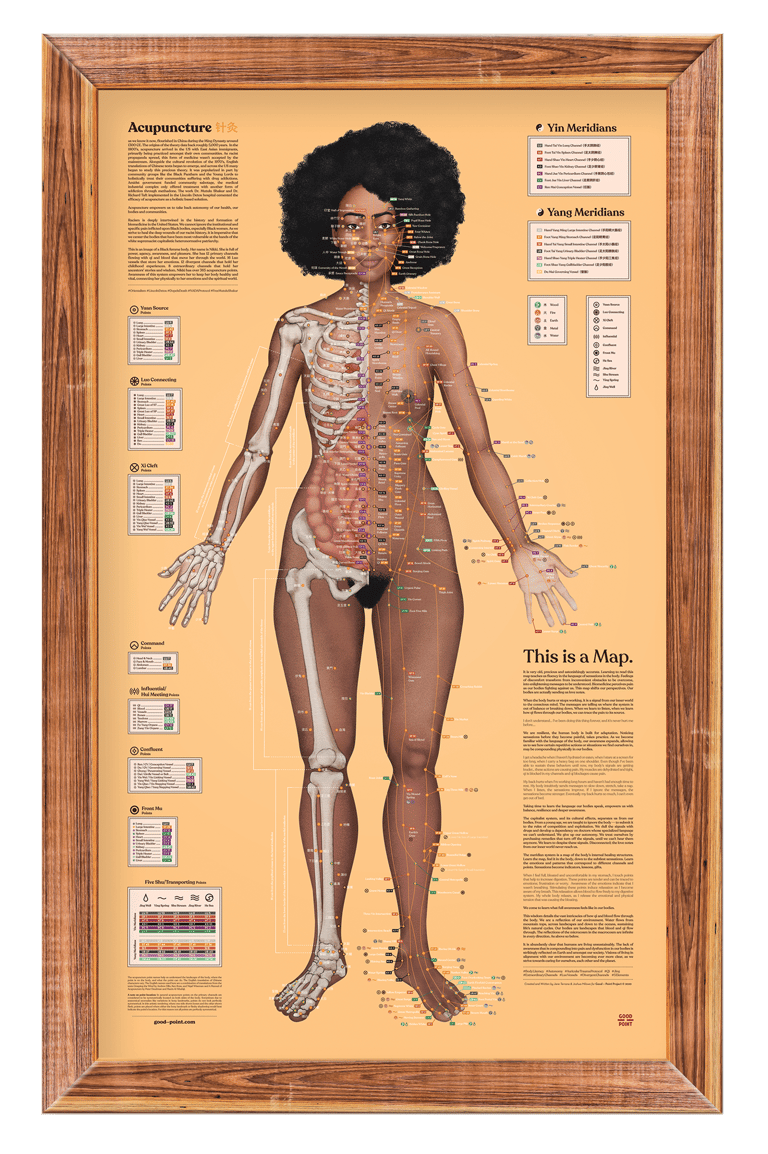

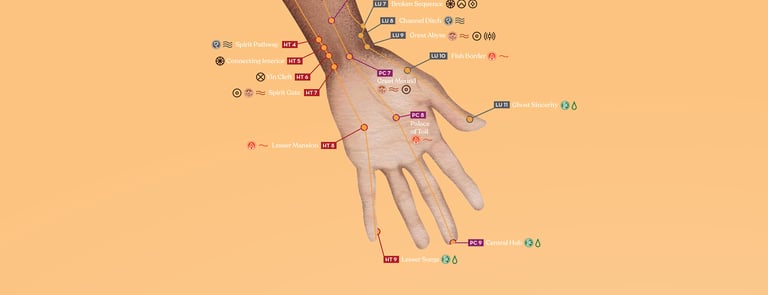

From the lived experience of not seeing diverse bodies being represented in acupuncture diagrams, acupuncturist Jane Terrana and graphic designer Josh Milowe designed a first-of-its-kind acupuncture diagram that shows the body of a black woman, on which the acupuncture points and meridians are mapped. This intervention changes the course of the history of the invisibility of black bodies in anatomy, but it also positions the diagram as a map, in its capacity to guide awareness and self-healing processes.

As expressed by Jane and Josh, "the basic premise is that the body is giving us signals all the time. Through acupuncture, and guided by this body map, we can learn to listen. It's as if the body is sending love notes. If we listen to the body, it will stir us in the right path, but we learn to ignore the signals, not learn to listen". The intention of the Good Point Project is then to make body awareness accessible to everyone, even if they are not engaged with acupuncture. We discussed the importance for young generations to tap into the discovery of their bodies, and just as acupuncture, the poster strikes the balance between simplicity and complexity, generating new relationships and moments of contemplation with viewers.

Mapping the interconnections within the body, and of the body with larger systems, are some of the incredible achievements of the project. On the right, the poster reads: "This is Nikki. She is full of power, agency, awareness, and pleasure. She has 12 primary channels flowing with qi and blood that move her through the world. 16 Luo vessels that store her emotions. 12 divergent channels that hold her childhood experiences. 8 extraordinary channels that hold her ancestors’ stories and wisdom. Nikki has over 365 acupuncture points. Awareness of this system empowers her to keep her body healthy and vita, connecting her physically to her emotions and the spiritual world".